How to Manage Overdose Risk During Heatwaves and Illness

Why Heatwaves Make Overdose More Likely

When the temperature hits 24°C (75°F) or higher, the risk of overdose doesn’t just go up-it spikes. This isn’t speculation. A 2010 study from Columbia University analyzing over 15 years of New York City death data found that for every week the heat rose above that threshold, accidental overdose deaths jumped significantly. The connection is real, measurable, and deadly.

It’s not just about being hot. Your body is fighting two battles at once: keeping cool and processing drugs. When you’re using stimulants like cocaine or meth, your heart is already working harder. Heat adds more pressure. Your heart rate can increase by 10 to 25 beats per minute just from the heat alone. Add drugs on top, and that number can jump another 30 to 50%. That’s a dangerous combo. Your body can’t handle it.

Dehydration makes it worse. Even losing just 2% of your body weight in fluids-something easy to do in a heatwave-can concentrate drugs in your bloodstream by 15 to 20%. That means a dose you’ve used safely before suddenly becomes too strong. You didn’t take more. Your body just didn’t have enough water to dilute it.

For people using opioids, heat slows down your breathing. Normally, your body adjusts to keep oxygen levels steady. But in high heat, that natural safety mechanism weakens by 12 to 18%. You might not even realize you’re stopping breathing until it’s too late.

Who’s Most at Risk

If you’re experiencing homelessness, your risk multiplies. In the U.S., about 580,000 people are homeless on any given night. Nearly 40% of them also struggle with substance use. These individuals often have no access to air conditioning, no way to stay hydrated, and no safe place to rest during extreme heat.

People taking medications for mental health conditions are also at higher risk. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants don’t work as well in high heat. Some even become more toxic. This affects people in recovery who rely on these drugs to stay stable. When the heat hits, their symptoms can flare up, making them more likely to use drugs to cope.

And it’s not just big cities. Places like the Pacific Northwest, which rarely see extreme heat, see overdose risk rise faster than in places like Arizona or Texas. Why? Because people there aren’t used to it. Their bodies haven’t adapted. A heatwave that feels normal in Phoenix can be deadly in Seattle.

How Heat Changes Your Body’s Response to Drugs

Your body has a built-in system to regulate temperature. But many drugs interfere with it. Cocaine, methamphetamine, and MDMA block your ability to sweat. That’s bad. Sweating is how you cool down. Without it, your core temperature can climb dangerously fast.

Heat also messes with your judgment. When your core temperature rises just 1.5 to 2°C (2.7 to 3.6°F), your brain’s ability to make decisions drops by 25 to 35%. You’re more likely to use more than you planned. You might forget to check in with someone. You might skip hydration. You might use alone.

For people on medication-assisted treatment like buprenorphine, heat can reduce how well the drug works. At temperatures above 30°C (86°F), its bioavailability drops by 23%. That means you might feel like your dose isn’t working-and take more. That’s how overdoses start.

What You Can Do: Practical Harm Reduction Steps

There are real, simple steps you can take to lower your risk during a heatwave. You don’t need a fancy solution. Just a few changes can make a big difference.

- Reduce your dose by 25 to 30%. Even if you’ve used the same amount for years, heat changes how your body processes drugs. Lowering your dose isn’t weakness-it’s strategy.

- Use with someone. If you’re alone and something goes wrong, no one knows to call for help. Even if you’re not comfortable talking about it, having someone nearby can save your life.

- Hydrate constantly. Drink one cup (8 ounces) of cool water every 20 minutes. Don’t wait until you’re thirsty. Thirst means you’re already dehydrated. Electrolyte packets, like those used for athletes, can help replace what you lose through sweat.

- Stay cool. Find shade. Use a fan. Wet a towel and drape it over your neck. If you have access to a public cooling center, go. Libraries, community centers, and some pharmacies offer free air-conditioned space during heat emergencies.

- Check your meds. If you’re on any prescription drugs-especially for mental health-talk to your provider before a heatwave. Ask if they need adjusting. Don’t guess.

What Communities and Services Can Do

Change doesn’t just happen at the individual level. Systems need to catch up.

Philadelphia started handing out cooling kits during heatwaves: misting towels, electrolyte packets, water bottles, and info cards on overdose prevention. They distributed over 2,500 in a single summer. The result? Fewer heat-related emergency calls.

In Vancouver, they created seven air-conditioned respite centers next to supervised consumption sites. People could get clean water, rest, and medical help-all without judgment. During the 2021 heat dome, overdose deaths dropped by 34% compared to previous years.

Maricopa County in Arizona trained volunteers to check on neighbors during extreme heat. Many of them carried naloxone. In 2022 alone, they made over 12,000 wellness checks and reversed 287 overdoses.

But here’s the problem: only 12 out of 50 U.S. states include people who use drugs in their official heat emergency plans. That’s a failure. Heat isn’t just a weather event-it’s a public health crisis for vulnerable communities.

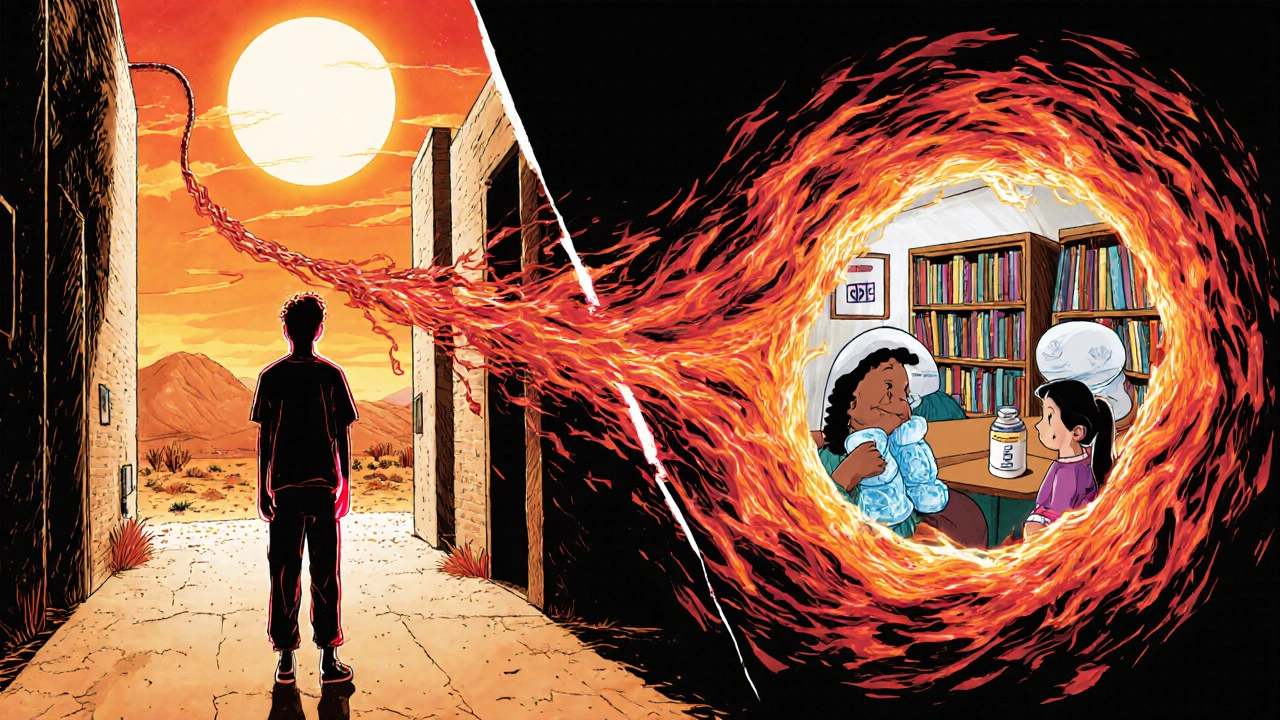

What to Do If Someone Overdoses in the Heat

If someone collapses, is unresponsive, or has slow, shallow breathing:

- Call emergency services immediately. Say, “I think this is an overdose, and it’s hot.” That helps responders prepare.

- Move them to a cooler place. Shade, a building, anywhere out of direct sun.

- Give naloxone if available. It works even if the person used stimulants. It won’t hurt them.

- Start CPR if they’re not breathing. Don’t wait for EMS. Every second counts.

- Keep them cool. Wet their skin, fan them, put ice packs on their neck, armpits, and groin.

Don’t assume they’re just “passed out.” Heat and drugs together can kill fast. Acting quickly saves lives.

Why This Matters Now

By 2050, the number of days above 24°C could increase by 20 to 30 per year. That means more people at risk, more overdoses, more deaths.

The Biden administration has allocated $50 million to fix this. By December 2025, every state health department must include overdose risk in their heat emergency plans. That’s progress. But it’s not enough. We need local action now.

It’s not about judging people who use drugs. It’s about recognizing that heat doesn’t care who you are. It just makes everything harder. The people most at risk are often the ones least likely to be protected.

Fixing this isn’t just about saving lives. It’s about fixing the gaps in our system-the shelters that turn people away, the police who take away cooling supplies, the health services that don’t ask about heat.

Can heat make drugs more dangerous even if I don’t use stimulants?

Yes. Even if you use opioids or other depressants, heat reduces your body’s ability to regulate breathing and temperature. Your heart works harder, you get dehydrated faster, and your drugs become more concentrated in your blood. This increases overdose risk regardless of the drug type.

Is it safe to use drugs in an air-conditioned space?

Being in a cool environment reduces some risks-like overheating and dehydration-but it doesn’t eliminate overdose risk. The safest choice is still to use with someone present, reduce your dose, and have naloxone nearby. Air conditioning helps, but it’s not a safety net.

Why do some shelters turn away people using drugs during heatwaves?

Many shelters have rules against drug use, often due to lack of staff training, fear of liability, or outdated policies. But during heat emergencies, this puts lives at risk. Some cities are changing this-like Vancouver, where respite centers are co-located with harm reduction services. No one should have to choose between safety and shelter.

Can I get naloxone without a prescription?

In most U.S. states and in the UK, naloxone is available without a prescription at pharmacies, harm reduction centers, and sometimes even public libraries. Ask for it. It’s free or low-cost in many places. Keep it with you during heatwaves.

What if I’m on medication for mental health and the heat makes me feel worse?

Heat can reduce the effectiveness of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and increase side effects like dizziness or confusion. Talk to your provider before a heatwave. They may adjust your dose, suggest hydration strategies, or recommend temporary changes. Don’t stop taking your meds on your own.

Are there free cooling resources I can access?

Yes. Many cities open cooling centers during heat emergencies-libraries, community centers, and public transit hubs often offer air-conditioned space. Some harm reduction organizations hand out cooling kits with water, electrolytes, and misting towels. Call your local health department or search online for “heat emergency resources” in your area.

What Comes Next

If you’re someone who uses drugs, your survival during a heatwave doesn’t depend on luck. It depends on knowledge, preparation, and community. Know your limits. Hydrate. Use with someone. Carry naloxone. Speak up if your shelter or service provider isn’t helping.

If you’re a friend, family member, or worker in public health-don’t wait for policy to change. Start a conversation. Carry extra water. Share info. Advocate for cooling centers near drug services. Push for change where you are.

Heatwaves are getting worse. So must our response. The people most at risk aren’t invisible. They’re our neighbors. And they deserve to be protected-not ignored-when the temperature rises.

Florian Moser

November 22, 2025 AT 07:07Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest, most practical guides I’ve ever read on this topic. Lowering your dose by 25-30% during heatwaves? That’s not just smart-it’s life-saving. And the hydration advice? Spot on. Thirst is already late-stage dehydration. Drinking every 20 minutes isn’t optional-it’s medical necessity. I’ve shared this with my whole recovery group.

jim cerqua

November 23, 2025 AT 16:51THIS IS A MASSIVE COVER-UP. The government knows heat kills drug users faster-and they’re letting it happen on purpose. Why? To thin the herd. Look at the stats: 580,000 homeless? That’s not a crisis-it’s a demographic cleanse. And now they’re handing out ‘cooling kits’ like it’s charity? No. It’s a PR stunt to make us think they care. Meanwhile, the real solution? Legalize everything. Let people use safely. Stop the lies.

Donald Frantz

November 25, 2025 AT 01:37Can we talk about the Columbia study? It’s cited everywhere, but what was the sample size? Were they controlling for other variables like socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, or pre-existing cardiovascular conditions? The correlation is real, but causation needs more rigor. Also-why is 24°C the threshold? That’s mild. In Phoenix, it’s 40°C daily for months. Why isn’t the spike higher there? The data feels cherry-picked.

Sammy Williams

November 26, 2025 AT 10:42Man, I’ve been through a few heatwaves and I didn’t even realize how much it was messing with my head. I used to think I was just ‘tired’ or ‘stressed’-turns out I was dehydrated and my dose was hitting like a truck. Started drinking water every 20 mins like they said. Didn’t even feel like using as much. Big difference. Thanks for the reminder to use with someone. I’ve been solo too long.

Julia Strothers

November 28, 2025 AT 01:54Who funded this? The pharmaceutical companies? The same ones pushing antipsychotics that ‘become toxic’ in heat? They want you scared so you keep taking their meds. And now they’re pushing naloxone like it’s a miracle cure? Naloxone doesn’t fix the system-it just keeps the wheel spinning. They don’t want you healthy. They want you dependent. Heatwave? Just another excuse to keep the machine running.

Erika Sta. Maria

November 29, 2025 AT 04:53But... isn't heat just nature's way of filtering out the weak? I mean, if you're using drugs and can't handle a little heat, maybe you're not meant to survive? Like in the wild, only the strong live. Also, I read somewhere in a blog that humidity makes drugs more potent? Is that true? Or is that just a myth? I think we need to look at this from a Darwinian perspective...

Nikhil Purohit

November 30, 2025 AT 17:25Biggest thing people miss: it’s not just about the drug. It’s about the environment. If you’re sleeping on concrete in 35°C with no water, your body is already in survival mode. Add a drug? You’re asking for cardiac arrest. I’ve worked with outreach teams in Delhi during heatwaves-we gave out electrolytes, shaded mats, and water. People were shocked someone cared. It’s not rocket science. It’s basic human decency.

Debanjan Banerjee

December 2, 2025 AT 10:43Let’s be real: if you’re using opioids and it’s 32°C, your respiratory depression risk isn’t just ‘increased’-it’s exponential. The 12-18% drop in natural breathing regulation? That’s not a footnote. That’s a death sentence. And buprenorphine’s bioavailability dropping 23%? That’s not a side note-that’s a clinical emergency. People think ‘I’ve used this before’ means ‘I’m safe.’ Wrong. Heat doesn’t care about your tolerance. It resets the rules.

Steve Harris

December 3, 2025 AT 22:38I appreciate the depth of this post. The harm reduction steps are clear, actionable, and non-judgmental. I’ve been working in public health for over 15 years, and I’ve never seen a guide this balanced. The mention of cooling centers in Philadelphia and Vancouver? That’s the model we need nationwide. We don’t need punishment. We need infrastructure. And we need to stop treating people who use drugs as problems. They’re people.

Michael Marrale

December 4, 2025 AT 02:51Wait-so if I use in an AC room, am I still at risk? What if I use alone but the AC is on? Does that mean I’m safe? Or is it just a little less dangerous? And what if I don’t have AC? Can I just sit in front of a fan? I’m trying to figure this out because my cousin is going through this and I don’t want to scare him, but I also don’t want him to die. Help?

David vaughan

December 5, 2025 AT 09:02Just wanted to say… thank you. Seriously. I’ve been using for years, and no one ever told me heat changes how drugs work. I thought I was just getting ‘worse at it.’ Now I know it’s the weather. I carry naloxone now. I hydrate. I don’t use alone anymore. I’m still not perfect… but I’m alive. And that’s something. 🙏